8. The defeat of Piedmont and the end of the war

Click image to enlarge

Click image to enlarge

Questions

Description and Analysis

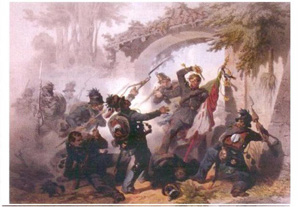

While Mestre was holding out under the Austrian siege and the republic was being established in Rome, within the government of Piedmont, presided over by the liberal catholic Vicenzo Gioberti, the idea was forming, shared by King Carlo Alberto, of reopening the war with Austria. The plan was to reconquer Lombardy and to rejoin the “liberated” cities, thus robbing the forces of democracy of initiative in the national war. The military situation had, however, changed from that of the previous year: Piedmont could no longer count on the contribution of volunteers nor of allied armies; the army was reduced in size to about 100, 000 men, mostly young recruits; the command of the army had been entrusted to a Polish general, with no knowledge of Piedmont customs and no experience of Italy. As usual, the plan of campaign envisaged the passage of the Ticino and a march on Milan, to take the Austrians in the rear; meanwhile General Ramorino was to defend Pavia and keep the Austrians at bay. Ramorino, however, did not keep to the orders he had received, allowing the Austrians to cross the Ticino at Pavia and enter Piedmont on 20th March 1849. The following day Ramorino was dismissed, tried and condemned to death for disobedience. Now Piedmont risked being occupied by the Austrian army, who were now in possession of Novara. In five days of fighting the rout was complete; the mirror image of the five glorious days of Milan. Faced with the very harsh conditions proposed by the Austrians, Carlo Alberto, who had perhaps for some time been thinking of renouncing his throne, announced his decision to abdicate in favour of his young son, Vittorio Emanuele, who was left to negotiate the peace. The terms of the armistice included the Austrian military occupation of a vast area of Piedmont until the signing of a peace treaty; the withdrawal of Piedmont troops from Tuscany, where a liberal government had been established in Florence, and its fleet from the Adriatic, where another dangerous hotbed of republicanism, Venice, still held out; a very heavy war indemnity of 75 million Lire. These onerous peace terms, even though they were later reduced by diplomatic bargaining, were not accepted without demonstrations of dissent: the mob in Genova, led by some university students, occupied the Palazzo Ducale; there was an uprising in Brescia at the outcome of the war and the city resisted the entry of the Austrians for ten full days. The strength of the national ideals and the desire for independence and self-determination on the part of the Italian population seemed to rise above the military setbacks and the will of the governments. Under the harsh conditions of the Austrian restoration at the end of the First War of Independence, the popular hopes which had had nourished the dream of ’48 did not die away when faced with the trials, the purges, the firing squads, the political divisions between the factions.

From 1847 onwards public demonstrations, political meetings, popular gatherings became the most widespread and important factors in the revolutionary process. The symbolic elements in the national discourse were nourished by the romantic literature of the preceding decades but, perhaps, even more so by a veritable explosion of musical works, both at folk level and by composers. Melodrama flourished during the season of revolution, serving as an element of cohesion and of patriotic propaganda. As happened in literature, where the historic novel chose heroes from the past to recount the present, dramas from the distant Middle Ages with strong echoes of the current scene were presented in the musical melodrama. An outstanding example was the “Battle of Legnano” composed by Giuseppe Verdi, presented with enormous success at La Scala theatre in Milan on 22nd January 1849 (that is, after the return of Austrian rule) and in Rome during the Republic.

THE BATTLE of LEGNANO, '49, by Giuseppe Verdi in M. Piave

(We all swear to defend her)

“We swear

to avenge the pillaged altars,

The women and children bled dry by the wicked.

We will chase these beasts from our native soil,

Let the cities be ours and be free.

We swear”

The end of the war and Austrian “Restoration” in Lombardy and the Veneto

The situation evolved, however, within a short time in a manner contrary to the hopes of the patriots. Pope Pius IX unexpectedly withdrew his troops through fear of a breach with catholic Austria and immediately afterwards so did King Ferdinand II of Bourbon. Carlo Alberto’s ulterior motive, the annexation of Lombardy, Veneto and the insurgent former duchies, became ever more obvious with the promulgation of plebiscites which confirmed with huge majorities the popular will in favour of “annexation” to Piedmont. The course of the war against Austria, after the initial Piedmont victories which were due, above all, to the units of volunteers, became more uncertain, allowing the Austrians to reorganise their forces and to unleash a violent counter-offensive, defeating the Piedmont army at Custoza. After retreating to Milan, King Carlo Alberto decided not to defend the city to the last and to withdraw back within the boundaries of his own state. An armistice with Austria was signed shortly afterwards; Lombardy was once more in foreign hands. The second phase of the war, which restarted the following year mainly through the wish of the Turin Parliament, was also negative for the Piedmont army (defeated at Novara), so much so that Carlo Alberto was forced to abdicate in favour of Vittorio Emanuele II and to withdraw to exile in Portugal. The Peace of Milan put an end to the war, leaving the Italian geopolitical situation substantially unchanged and completing the first phase of the process of national unification, that strongly inspired by liberal democratic ideals dominated by popular initiative.