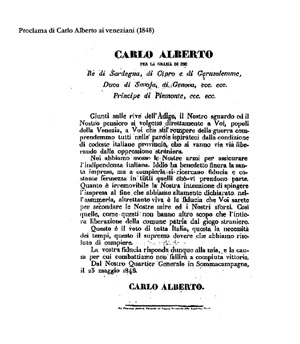

4. Carlo Alberto's Proclamation to the Venetians (25 May 1848)

Click image to enlarge

Click image to enlarge

Questions

Description and Analysis

Between February and March the revolutionary incidents, initially limited to the Italian peninsula, took on an international character. An insurrection broke out in Paris on 22nd February which forced King Louis Philippe to flee and led to the proclamation of a republic. On 13th March agitation began in Vienna where the situation deteriorated quickly to the point that the head of government, Metternich, was forced to resign and leave the capital: the granting of a constitution was announced three days later. The events in Vienna had immediate repercussions on the Empire’s Italian territories: by 17th March there were already public disturbances in Venice which quickly led to the formation of a provisional government; the following day there was an uprising in Milan and the discontent towards the Vienna government began to spread also in the eastern provinces. In this extremely critical situation for the government in Vienna, on 23rd March Carlo Alberto decided to intervene in Lombardy-Veneto with a declaration of war on Austria; thus began what would become known as, its official historical codification, the 1st War of Italian Independence (followed ten years later by a second war, the victorious outcome of which would lead within two years to the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy). Within a few days the Piedmont army reached Milan (which had already “freed” itself of the Austrians), where it was joined by other bodies of troops, sent by the Papal State, the Kingdom of Naples and by Tuscany, while other, voluntary militias were formed in several cities of the Po Valley with the intention of combining with the regular army of the Kingdom of Sardinia. The atmosphere seemed to be full of hope and collaboration such that, even Mazzini, who arrived in Milan on 7th April, declared his support for Carlo Alberto’s project in the name of achieving Italian independence. The idea which motivated all of the national-patriotic forces was that of cooperating in order to bring about, finally, the unity of the Italian people, joined for centuries by a shared language and culture but who had not yet found a unitary political entity: until that moment, Italy had existed in name only and the first step in building a nation state would be to free it of “foreign” rule. That was the plan which seemed to be motivating Carlo Alberto: to bring together all the available forces to drive the Austrian presence from Lombardy and Veneto. The future destiny of the new state and its constitutional form were, however, more uncertain since the patriotic ideals which inspired intellectuals and politicians were divided between support for the initiative of the House of Savoy and the suspicion, on the part of the republicans, that this might be, at base, a way of expanding the territorial boundaries of the Kingdom of Sardinia. (Questions 1-2).

Within a short space of time these hopes were, however, destined to fade on account of three further developments in the situation. The first concerned the military support from the other rulers on the peninsula which diminished as the days passed because of fears, nurtured principally by the Pope, of a rupture in diplomatic relations with Vienna. The second was the desire of Carlo Alberto to go quickly ahead with the annexation of the liberated territories in Lombardy, Veneto and the former duchies in central Italy to Piedmont; the operation was carried out by means of plebiscites which declared by very wide majorities the popular will to join Piedmont. The outcome of this hasty decision while the war was still in progress provoked protests from the republicans and democrats, and therefore from the majority of the volunteers who were taking part in the military operations. Carlo Alberto tried, therefore to convince the popular forces of his genuine adhesion to the national cause: if he were to lack the support of the “liberated” territories, the military operations against Austria would be hindered, with serious consequences for the outcome of the war. This is, in effect, what happened; after the initial successes, obtained above all by the strenuous resistance of the volunteers, the progress of military operations slowed until, on 22nd July, the Austrian counter-offensive began which led, three days later, to the defeat of Piedmont at Custoza in western Veneto. After retreating to Milan, Carlo Alberto decided not to defend the city and to retire within the frontiers of the Kingdom of Sardinia. An armistice with Austria was signed on 9th August: all of the “liberated” territories returned under Hapsburg dominion, with Venice, alone, continuing to hold out to the end. (Questions 3-4).

The uprising in Milan: “The Five Days”

The uprising exploded in Milan on 18th March, with unexpected support from the farmers in the surrounding rural areas, against the soldiers of Marshall Radetzky. After five days of very heavy fighting the Milanese patriots, with rudimentary weapons and protected by barricades erected by the population as best they could, managed to free the city and the Austrian troops were forced to retreat towards the Veneto. A Council of War was formed under the leadership of Carlo Cattaneo, one of the most clear thinking intellectuals of the Risorgimento, and Enrico Cernuschi. The more moderate members of the city government invited Carlo Alberto, King of Sardinia, to back the revolt.