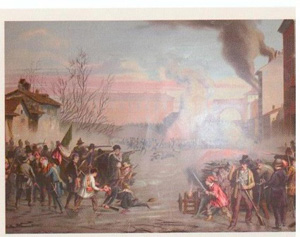

6. 18th March 1848: “The Five Days of Milan” begin

Click image to enlarge

Click image to enlarge

Questions

Description and Analysis

The outbreak of the Milan uprising was quicker and quieter than those in other Italian cities: right up to the afternoon of the eve, the reports about unrest and demonstrations elsewhere in the Empire were still hazy and uncorroborated. However, when a messenger brought confirmation of the rumors several groups met and hastily arranged a demonstration outside the town hall calling for freedom of press, a civil guard, the convening of national representatives and the neutrality of the army. The protesters' intentions were peaceful, but, given the impromptu nature of the event nobody could have made predictions about the way things would turn out. On March 18th twenty thousand people gathered in front of the Chief Magistrate's, that is to say Mayor's, Seat. They gathered yelling their demands, but entirely spontaneously, without any kind of political leadership. At this point, the Chief Magistrate himself, Gabrio Casati, took charge, stepping forward as spokesman for the protesters' demands with the Austrian Government. Casati was a moderate liberal and philo-Piedmont, he was eager to stop the uprising getting out of hand and do so without breaking the law. Unhappily, as he made his way present the people's demands at the Austrian headquarters another marching mob had already raided it, killing two guards, wrecking the rooms and defacing a portrait of the Emporor. Thanks to Casati's prompt action the vice-president of the imperial government was whisked to safety where, however, he was forced to sign 3 decrees: one conceding a civil guard, one to sack the head of police and the third compelling the police force to hand their arms over to the civil guard. These measures were not enough to bring the uprising to a halt. The people of Milan at this point were building barricades with whatever was close to hand – a cart, pews from a nearby church, carriages taken from the stables of the governmental buildings. No-one heads the uprising, the city as a whole took up arms ,without prompting, but all bearing the tricolour as a symbol of their claim to independence. One of the most brilliant intellectuals of the time, anti-Piedmont and supporter of the federal democratic scheme, Carlo Cattaneo, to begin with sees the uprising as an unrealistic enterprise against the overpowering Austrian army. He was proven wrong, when the Austrian army began to struggle under the onslaught and when they tried to prevent provisions reaching the Milanese they found all routes by barricades springing up all over the city. There are between six hundred and a thousand of them, plus people shooting, showering them with roof tiles or dousing them with boiling water from windows above. Throughout the city the battle raged, the city-dwellers seeking out weapons to arm themselves, even ransacking the The Scala opera house for the singers' stage arms. (questions 1 -2 -3).

Against the Austrian authorities expectations the rural areas join the uprising “The city” as an Austrian officer reports “is surrounded by thousands of armed and roused farmers shooting at the soldiers on the bastions who are already under fire from within”. After five days of intense fighting between the patriots with their makeshift weapons sheltering behind the barricades and the Austrian army on the other side, Milan is freed: the Austrian authorities go into retreat along with the army. In the meantime, inside the city a provisional government is set up, headed, once again by Casati, who decides to postpone any decision regarding the form of government until independence is achieved. Three days later the Piedmont troops arrive in Milan. The common people paid a high price for their involvement in the uprising: of the 250 identified fallen, craftsmen and workmen account for 160 of them, there are 25 servants and valets, 14 farmers, 29 shopkeepers, 38 women, the vast majority of whom were workers, but only 3 landlords, a few engineers, a priest and a handful of students. (question 4).

Other Information

A full account of the events of ’48 in Venice, Milan and Rome can be found in Cristina Trivulzio di Belgioioso's ,Essay on the Italian Revolution in 1848. Belgioioso was a zealous patriot and active supporter of the revolutionary cause. The text is available at: < a href="http://www.url.it/donnestoria/testi/belgioioso/rivoluzioni.htm">http://www.url.it/donnestoria/testi/belgioioso/rivoluzioni.htm

The rising spreads to other Italian cities

Between the end of March and April 1848, following the insurrections in Venice and Milan, in the minor duchies of Parma, Piacenza and Modena the rulers also ceded to provisional governments of national-liberationist inspiration which organised expeditionary corps to send to the aid of the Piedmont army. In the following months these cities declared, almost unanimously, through plebiscites their willingness to be annexed to the Kingdom of Sardinia. As a result of these annexations the first “Italian” administration was formed on 27th July, a government composed of representatives of different Italian cities to whom the various ministries were allocated; this scheme was dropped as a result of the disastrous progress of the war against Austria.