2. Amateur photographs

2a. War photography competition: “The French attack, Germans surrender...”, published in the weekly newspaper Le Miroir, Sunday, June 27, 1915.

Click image to enlarge

Click image to enlarge

Vocabulary

Shrapnel: Named in the late eighteenth century after its inventor, Henry Shrapnell, the shrapnel is a shell filled with a mixture of powder and musket balls released at the moment of the explosion, used mainly against infantry. The term is often used inappropriately by extension to describe the fragmentation of shells during the explosion.

Presentation

In the issue of the newspaper of March 14, 1915, Le Miroir launched the War Photography Contest. The contest is open to amateur photographers (Article 2), "authors of the most striking photographs of the War." The photographs must be recent and supplied with "clear indications concerning the date, place and subject of each of photograph" (Article 6).

In May 1915, Le Miroir launched a monthly contest in parallel, with three awards, addressed to amateur photographers requiring that no special effects should be used (Le Miroir, May 23, 1915, p. 3) and a guarantee of authenticity.

Taken during the offensives of the spring and summer 1915 in Artois, near the plateau of Notre-Dame-de-Lorette, these photographs are little more than a photographic report of the battlefield conditions and a stereotypical representation of the battlefield: no man’s land and devastated landscapes, trenches, assault and omnipresent death.

Questions 2a

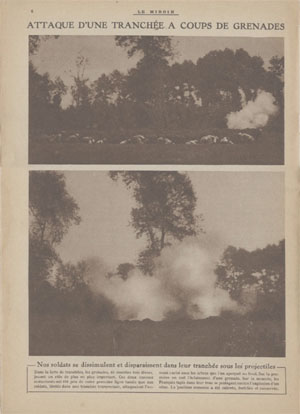

2b. A photograph “Trench warfare with grenades” published in the weekly newspaper Le Miroir, Sunday, August 1, 1915

Click image to enlarge

Click image to enlarge

Photograph caption

“Our soldiers hide in their trench before it is hit by a missile”

“In the trench warfare, grenades of very different kinds play an increasingly important role. Both of these interesting pictures were taken from the first line when soldiers, hidden in a transversal trench, were fighting against the enemy hidden under the trees whom we hardly see in the background. On the first picture, we can see the explosion of a grenade. On the second one, French soldiers, crouched in their trench, are protected against a bomb explosion. The enemy’s position was captured, fortified and preserved.”

Presentation

Learning the story of the battle from the pictures, the reader experiences the battle directly, finding themselves in the midst of smoke, shrapnels and grenades, which obscure much of the field; they share the heroism and the fear of the attackers, and, of course, their final victory: "The enemy position was captured, fortified and preserved."

Questions 2b

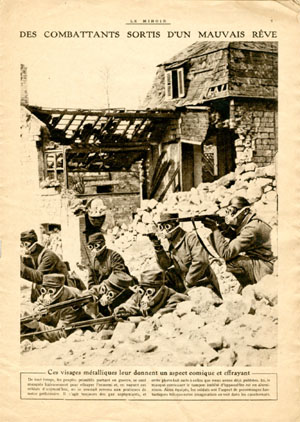

2c. A photograph: “Warriors in a nightmare” published in the weekly newspaper Le Miroir, Sunday, August 22, 1915

Click image to enlarge

Click image to enlarge

Photograph caption

These metallic faces give them a comic and frightening look

“Primitive people going to war have always hidden their faces behind hideous masks to frighten the enemy. Seeing these soldiers today, it seems that they are reviving our prehistoric habits. Yet, it is now a matter of suffocating gasses and this photograph is a continuation of a series of photographs we have already published. With this equipment, our soldiers look like fantastic characters we see in our nightmares.”

Vocabulary

Hyposulfite: From April 1915 in the Ypres sector, the German army used chlorine as a suffocating gas; from June and July they used several other irritant and toxic gases, from July 1917, inter alia, the mustard gas (dichlorodiethyl sulfide) or “yperite”. With the use of sodium hyposulfite, chlorine neutralizer, it was possible to make masks which, combined with glasses, used to protect soldiers.

Presentation

This photograph illustrates the search by the press for an original image, the search for the sensational. Through such phrases as "primitive people" or "prehistoric habits" the legend becomes a part of the scientific and popular debates of the time upon civilization and race. At the same time, the photographs, with their unrealistic undertones, strongly indicate the difficulties of daily life in the destroyed cities and the horrors of war visible in the use of gas by the belligerents.

Questions 2c

Historical Context and Analysis

The ideas of readers’ contribution, journalistic competition, and an interaction with the audience which resulted in the need to provide the texts for newspapers with illustrations were a novelty in 1914. Before the founding of the Photographic Section of the Army, the illustrated press lacked documents supposed to answer the reader’s expectations. The photographs bought by “Le Miroir” from the SPA (Army Photographic Section) did not constitute the majority of published photographs. According to Joëlle Beurier (see p.22) between May 1915 and end of September 1917, “Le Miroir” bought 233 photographs from the SPA, at the same time publishing thousands of other photographs.

In August 1914, “Le Miroir”, as in many other illustrated newspapers, focused on the presentation of mobilization rather than on the pictures from the front lines: each perceptive reader or photography lover can immediately detect the artificial nature of the high angle shot which clearly exposes the photographer’s intentions.

In the issue of March 14, 1915, “Le Miroir” launched a war photography competition. The competition was addressed to photography lovers (article 2) - “authors of the most striking war photographs”. Negatives had to be recent and be supplied with “precise indications of the date, place and subject of each negative” (article 6). “Le Miroir” announced the first prize at the amount of 30,000 FF for the best photograph published from the beginning of WWI to the end of hostilities.”

In May 1915, “Le Miroir” also launched a monthly competition with respective three prizes of 1000, 500 and 250 FF. In the announcement, it is stated:

“We remind the photography lovers that no posed photographs and no rigging of any kind are allowed and, as for publishing the photographs, all the warranties of authenticity and origin are requested” Le Miroir, May 23, 1915, p.3.

In “Le Miroir”, issue number 75 dated May 2, 1915, the following statement was published: “The most precious war photograph [...] was taken at the end of September 1914 by a sub-lieutenant of dragoons who captured the exact moment when a bomb fell between two lines of soldiers [...]”. The issue released after the awarding of the prize, in which the photograph was published, included a copy of the text of the letter of the sub-lieutenant who was the author of the photograph and who provided precise information concerning conditions in which it was taken:

“At the end of November 1914, the dragoons executed this task, a few days after a bayonet attack. They had been ordered to remain in a wood where the enemy was hiding. It was around 3pm, the weather was horrible and the meadows damp. I was running with my camera prepared for photographing this first charge of dragoons armed with bayonets when a bomb exploded in front of me killing two men which I have captured on the photograph. I had just enough time to press the button when the bomb exploded and I had to continue the charge; I recalled that I should advance the roll only at the end of the day after the conquest of the wood.”

Approximate place, date and technique were specified as well.

It is not obviously true that only “photography lovers were admitted to take part to this competition”. Yet, some of them, like Blaise Cendars (see document 3) and the famous sergeant René Pilette, sent many photographs to the newspapers and regularly contributed to the press (see Joëlle Beurier “Learning the event” Photographic Studies n°20, June 2007 pp. 68-63 (http://etudesphotographiques.revues.org/index1162.html)

Apart from the information provided in the caption which locates the presented events near the Notre-Dame-de-Lorette plateau during the attacks led in the spring and summer 1915 in Artois, we do not know anything about the photographs of the 2a document. However, the photographs fit well into the convention of the photographic report; it also follows and reinforces the established stereotypical representation of the battle field: the no man’s land and devastated landscapes, trenches, omnipresent assault and death that is either implicitly suggested or shown directly with its most horrible details.

The aim of both photographs of the 2b document, without an indication of the place or the date, is not so much =to inform the readers (the third page of the weekly newspaper gives daily news front different fronts) but to give them a close-up of the military events. In spite of the differences in size, the use of chronological development of action in several photographs with a travelling effect the arrangement of photographs into sequences, and especially the depictions of explosions together with the smoke give the reader an impression of entering the photographer’s shoes and imagine the whole course of events. Through the picture story, the reader experiences the battle; finding themselves surrounded with the smoke of bombs and grenades which hides a large part of the field, the reader shares the heroism and fear of fighters and obviously the final victory. The caption of the photograph: “The enemy’s position was captured, fortified and preserved” is mainly descriptive - all the attributes of the enemy have been erased, which makes the caption neutral, almost topographic; it only refers to “the enemy’s position”.

The photograph of 2c document exemplifies the search of the press for an original, sensational, and a bit humoristic or even ironic picture. The terms: “primitive people”, and “prehistoric habits” were very conspicuous in the period where the issues of “primitive” knowledge”, “civilisation degree”, “social hierarchy”, etc. were frequently the subjects of scientific as well as popular debates. Similarly as the images of mutilated, decomposed, partially buried corpses, which were widely published in “Le Miroir” from 1916, this indicates the relativity of censorship exercised by the Press Office as well as by the army. But at the same time the photography with its unrealistic undertones emphasized the daily problems in destroyed towns as well as the war horrors when fighters used gas.

Questions 2a

- How did the weekly newspapers get direct reports from the front?

See the presentation of documents. - What were the requirements of weekly newspapers guaranteeing the photograph’s authenticity?

See the presentation of documents. - What was the position of the photographer while taking photographs and what did he offer us to see on the battlefield?

The first photograph was taken from the ground slightly upward, which suggests that the photographer was standing at the back on the no man’s land between the opposing trenches; the second photograph was taken from a different position. It seems to have been touched up in many ways. - Why did the weekly newspaper print the original contact prints beside the enlargements?

The contact print added to the enlargement in the publication is supposed to show that the photograph was authentic. But the panoramic shot sheds doubt on the technical conditions of such photographs in action. - Provide the clues that show that these photographs could have been altered during exposure or touched up before printing.

Shells, berets, the attitude of Germans who give up... - Was the situation at the front presented faithfully?

See the presentation of documents.

Questions 2b

- What makes this photographic story a testimony?

See presentation. - What are the tactics used on this page to create empathy with fighters and to render the reality of the fight?

Despite the proximity of the action and the photographer’s participation in the war, photographs of WWI do not present the confrontation of two armies in a fashion typical of battle paintings. By presenting the chronological development of a fight, the arrangement of the materials on the page enables the reader to see different phrases of the action and allows them to observe it from the point of view of the photographer and imagine the intermediary scenes. The size difference of the pictures, which shows that the photographer has moved forward, only acts as a focalisation. “Le Miroir” develops this kind of photographic sequences, which were of particular interest to Joëlle Beurier (see p.67) who states: “juxtaposition of negatives depicting the same event, arranged into a story by means of captions, makes up a narrative with its own temporality which introduces the reader into the fight and the bomb attack. The reader becomes a spectator and is then led into the places of history by the photo report. The boundaries between the front and at the back disappears thanks to the first-hand documentation. This kind of a photographic narrative offers more than an illusion of participating in real-life events. It facilitates the merging of roles and the disappearance of the boundaries and, more specifically, abolishes the language limits which inhibit communicating one of the hardest war experiences - a bomb attack.” - Did height cropped pictures, in this photographic sequence, make sense for a reader of the newspaper in 1915? Do they make sense nowadays?

See the previous question.

Questions 2c

- What are the elements that show that the soldiers posed for the photograph?

Obviously, apart from the photographer’s position (the point of view, angle, framing...), the posture of many soldiers and the way they hold their weapon is unnatural. However, this does not change the value of the photograph as an account of destructions, the fight in the ruins, the use of gas and the protection against it. - However, in what way does such a photograph provide the 1915 readers as well as the modern readers with information on war conditions?

See the previous question. - What view of the war does the vocabulary connected with dream and war primitivism used in the photograph title and caption reinforce?

During WWI all forms of the representation of war have changed. The living conditions of soldiers and civilians from the destroyed regions were unbelievably bad; they were beyond the imagination of civilized people, but this should not be surprising since the unprepared troops had to face the opponents’ new inventions. “Le Miroir” often revealed these discrepancies, sometimes showing the problems with supplies suffered by the troops.

Photograph caption

« Snapshots of Notre-Dame-de-Lorette Plateau during the last fights (zoom x60). To the right, small contact prints of photographs. »

“Photographs which show fights are very exceptional and obviously imperfect. The photographer has no time and bad conditions to take a well-exposed photo. Taking such a photo verges on a miracle. Soldiers can be at any time killed or injured by bullets or shrapnels. In spite of danger, one of them is calm enough to take photographs. These two curious photographs were taken nearly at the same time, during the violent fights near Arras, in the north of France. The first photograph shows a bayonet attack, with the soldiers bent over submachine guns trying to protect themselves with their bags, against shrapnels which often burst above them. On the second photograph, shot in a trench, we can see four German soldiers who have surrendered their position and are taken prisoners. The one to the left has raised his arms up to show he has no weapon. On the other side of the lens, French troops are calmly waiting for the prisoners in the trench.”