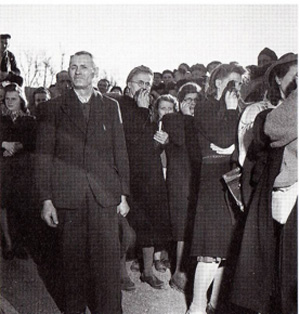

« Dans la cour du crématoire, en tout cas, un lieutenant américain s’adressait ce jour-là à quelques dizaines de femmes, d’adolescents des deux sexes, de vieillards allemands de la ville de Weimar. Les femmes portaient des robes de printemps aux couleurs vives. L'officier parlait d'une voix neutre, implacable. Il expliquait le fonctionnement du four crématoire, donnait les chiffres de la mortalité à Buchenwald. Il rappelait aux civils de Weimar qu'ils avaient vécu, indifférents ou complices, pendant plus de sept ans, sous les fumées du crématoire.

Votre jolie ville, leur disait-il, si propre, si pimpante, pleine de souvenirs culturels, cœur de l'Allemagne classique et éclairée, aura vécu dans la fumée des crématoires nazis, en toute conscience !

Les femmes- bon nombre d’entre elles, du moins – ne pouvaient retenir leurs larmes, implorant le pardon avec des gestes théâtraux. Certaines poussaient la complaisance jusqu’à manquer de se trouver mal. Les adolescents se muraient dans un silence désespéré. Les vieillards regardaient ailleurs, ne voulant visiblement rien entendre. »

Presentation 3a

This text written by Jorge Semprun describes the visit imposed on German civilians of the nearby town of Weimar after the liberation of Buchenwald by the American army. Lt Walter Rosenfeld, a German-born American soldier, was the guide for this visit. Here is what we learned about him by J. Semprun: “He was five years my senior, so he was 26. Despite his uniform and his American citizenship, he was German. I mean he was born in Germany in a Jewish family in Berlin, emigrated to the US in 1933, when Walter was 14. He had opted for the US citizenship to bear arms, to make war against Nazism…”